Dungeons of Freeport Log 1 – Roguelike?

Okay, so I’m doing a new thing. It began when I installed Rogue and Nethack on the test server that my awesome testers help me with Swords of Freeport on. One quipped, “Dungeon crawl in Swords of Freeport when?”

I promptly began coding.

This… isn’t an addon for Swords of Freeport. It’s a stand-alone roguelike game (or, I suppose, maybe roguelite depending on JUST how strict you feel like being over which features from the original Rogue are required or not). However, the principle twist is this:

Like Swords, it is designed to be played once a day. Think of it as a ‘once a day dungeon delver’. Like Swords of Freeport, where you get a set number of ‘actions’ per day, in this you will get a single dungeon delve each day. You can spend time equipping and sorting things out before you go in, then you pick one of several dungeons that are generated each day and… go for it.

In the time since, it’s grown a lot. From that first very simple ‘you can move an @ around a simple maze’, I’ve written a design doc, bounced ideas off designer friends, and coded many many thousands of lines of C++, using nothing but the standard library and ncurses.

It’s… a game now. A proper game, and very very much a rogue…adjacent.

I am not going to go into a huge amount of detail about the meta-game I’m designing, nor the combat mechanics, as they’re both still in flux and I don’t want to describe something in a blog post only to change it 7-8 times before arriving at the final product – but I am going to talk a bit about the systems I’ve been designing, and the techniques I’ve used (or tried using and rejected) for things like procedural dungeon generation.

The Mechanics

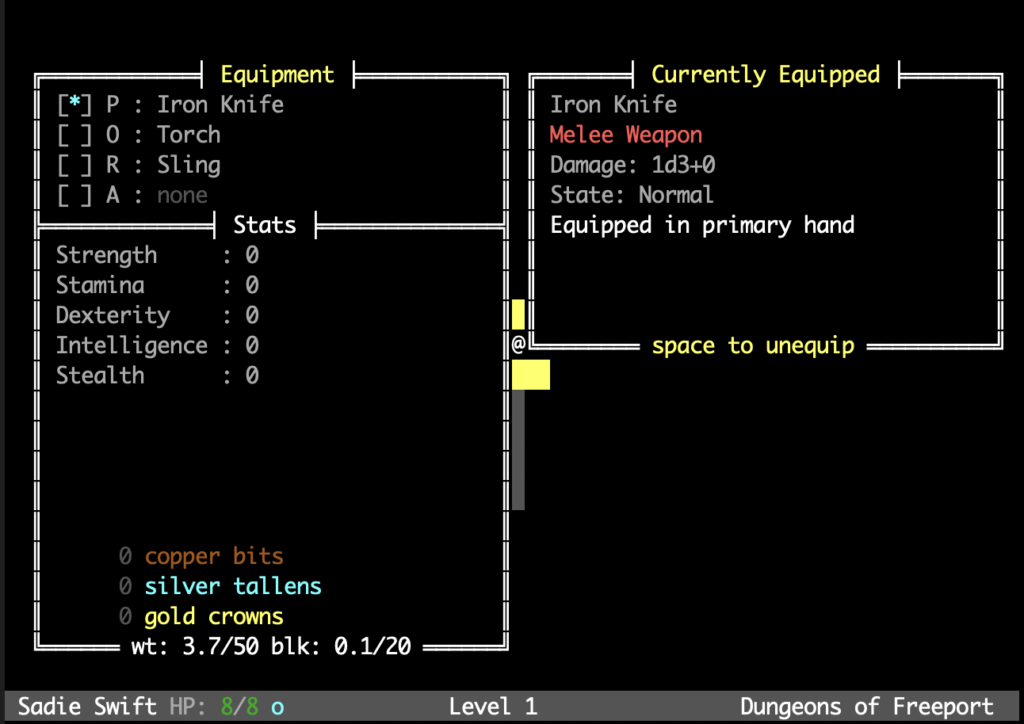

I’ve decided to go for a more simulatory experience. The player must manage the bulk and weight of items they carry – even including how much coins or ammunition for ranged weapons take.

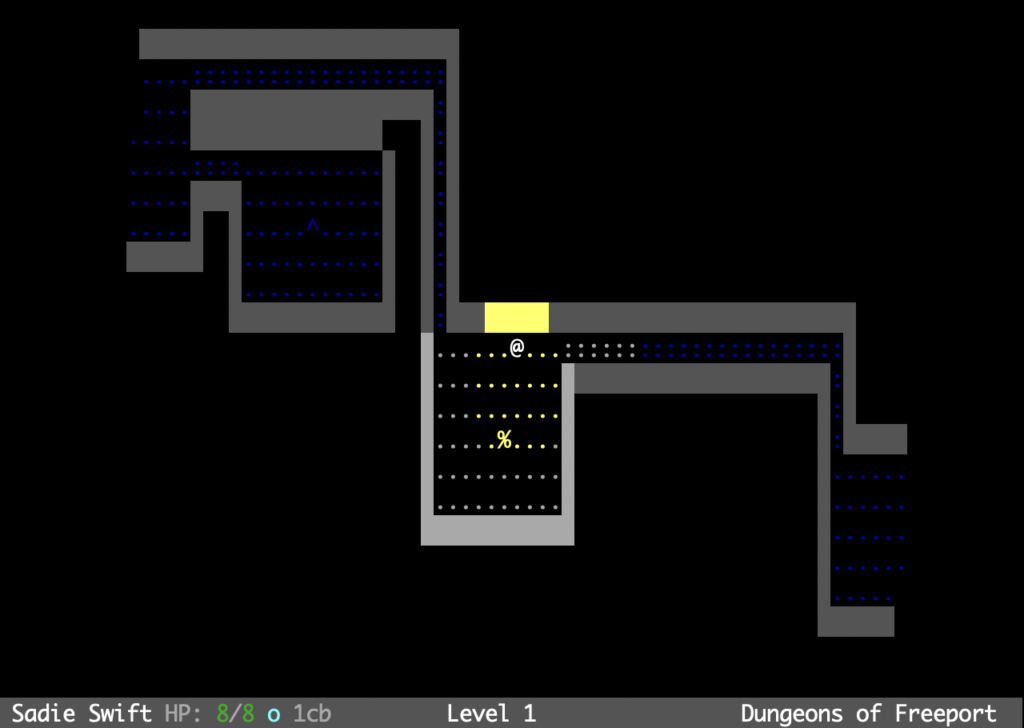

Characters have a very minimal ability to see in the gloom of a dungeon, and must choose to equip a torch to mitigate this. This provides (as seen above) a nice glowing yellow area around the player, and boosts their visible range. It even lets them identify secrets (such as passages in doors, or cracks in stone that indicates it might be broken through using a mining pick.

It comes with a down side though – it gives away your position to enemies more easily.

Sound also travels in the game. It’s far from a hardcore simulation, but actions (such as moving quickly, picking up items, or attacking a monster) will emit sound which could wake up a nearby sleeping monster from its slumber, or simply prompt an awake monster some rooms away to investigate the noise.

Monsters have a utility AI system (brilliantly described in this youtube video on Game Maker’s Tool Kit) designed to give them specific behaviours. For instance, some sleep lots; others not at all. Some prefer dark rooms and hide in places to ambush. Others meander quite aimlessly.

I am building these as modules that can be turned on or off, allowing me to generate 26 unique enemies that have more differences between them than who has what hit points.

I also intend to add things that can grow, be harvested, and crafted into other things (for reasons that will become more apparent when I talk amore about the meta-game sitting above each individual dungeon delve).

The final main systemic point – this is a turn based game. Being that stealth is a component of the game, with light and sound propagation being facets of it, I knew I wanted to keep it turn based to make it more of a tactical and strategic game, than one that would quickly devolve into clicking a lot. (This is said with love, Diablo! I promise.)

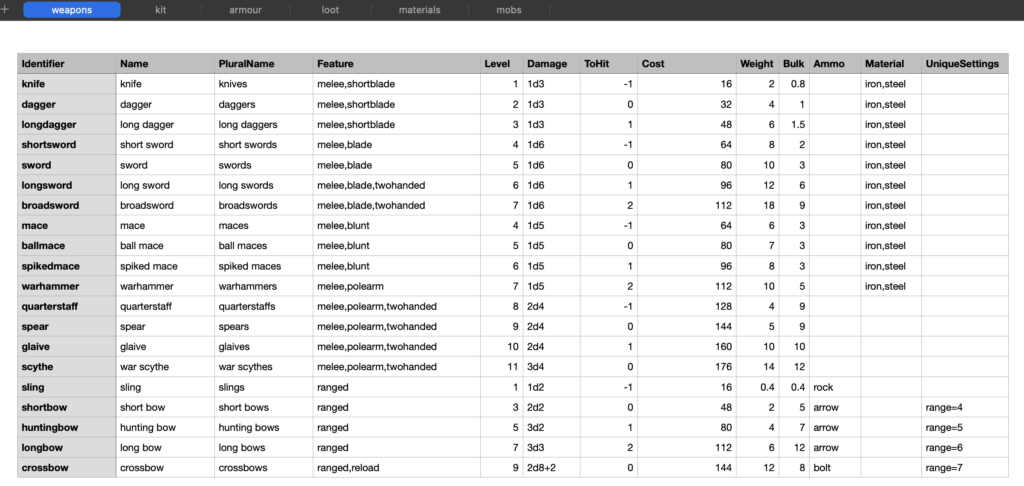

As for getting the data in… I decided on a fairly simple method: spreadsheets.

Given so much of the game is, for the designer, entering mass information about items, mobs, weapons, properties, etc, it made sense to make this process easy for me.

So the game data is all in a spreadsheet in Apple Numbers. I export it to a CSV, run a tiny python script to jam it into the right directories, and the game loads it from there.

The Interface

Visually, I am going to have two modes – low ASCII (that is, standard keyboard characters, such as what Rogue uses) and high ASCII, giving me access to fancier tools. You can see this below in the borders being used for the pop-up menu.

But it’s the pop-up menu that I want to talk about now…

Old school Roguelikes tend to utilise well… the whole keyboard. Or close to. Beyond moving your character, there are hotkeys all over the keyboard for anything from ‘quaffing’ a potion to ‘equipping’ an item.

That’s fine and good – that density is even part of what some hardcore roguelike fans love about them.

But I didn’t want to have to teach all this to new players. So I made a decision early on:

This game should be playable on a controller/gamepad. I’m not sure I’ll ADD support for them (it’d be annoying – I did briefly try with it) but I want an interface system that fundamentally sticks to arrow keys and up to 6-8 action buttons, ideally less if I can get away with it.

This does mean relying pretty heavily on menus – but that’s fine by me.

I’m even designing the game with the rendering and interface entirely separated by a coder layer to the back end logic. I’m not saying this means I am going to do a graphical version just… that it means I could, should I want to.

The Dungeons

Roguelikes are defined by their dungeons. From the plus, minus and pipe characters that make up the iconic dungeons of Rogue to the beautiful colours and patterns of Brogue, it’s what really sticks in my mind when I think of those games.

Now, I had done procedural content before in games. A little in Super Death Fortress and its sequel, but much more in my first game TownCraft. However, I never used particularly in-depth systems, and honestly the procedural work in the games was always a bit lacklustre.

My first dungeon creation tool was very simple – it’s what’s in there now. With the addition of some A* routines to make vaguely rational and rarely-intersecting passages between rooms, it’s enough to test the game as I design it… but not enough give the variety of dungeons I want.

That was when I began to look up articles on coding Roguelikes… and when I found out something: the roguelike community is really fucking cool.

Like, seriously – most every of the old classic roguelikes from the ’80s to the early ’90s is open source, and there are whole conventions (now digital and VERY accessible) with extremely talented develoeprs discussing the many techniques used to create their beautiful dungeons.

This sent me down a rabbithole it’s been hard to come out from.

First I tried BSP dungeon generation – which sounded nice and fancy in theory, but in practice didn’t really do what I wanted from my dungeons.

So I implemented random room generation. This system initially made me balk because some crappy part of my brain acts as though I’m coding these games for 8-bit microcomputers, rather than arm based supercomputers that somehow exist on a single chip.

The simple fact is that when making a text mode game (or even a simple graphical one) modern CPUs let you brute force things much faster than you’d ever get away with trying to make a Roguelike work on a 286 or 8086.

So I am going to use that.

My game requires visually and structurally unique dungeon types, so I am going to use a combination of canned rooms with random elements, cellular automata for caves, and a random room placement tool atop it all.

I’ve learned a LOT about things I only knew a bit of in the while coding this – and it only excites me to learn more as I go.

Making games is a catch-22 situation. You can make a game you always wanted to play… but you will never get to enjoy it as much as someone who didn’t have a hand in making it. Hell, you may not even be able to stomach playing it at all.

Procedural games are different. I can ENJOY playing this. Even now, with the very basic gameplay already in place, I am sometimes just loading up the game to go for a delve.

I always liked Roguelikes… but I think I just might like building them more.

(Until I have to try and make an ncurses game run on Windows… that’s going to be hell.)