Dungeons of Freeport Log 4 – Fun

There’s a lot going on with Dungeons of Freeport right now, and while I found myself musing on a few important things with a figurative rubber ducky, I decided this might be a good time to use my blog as such an item.

So, let’s get started with this concept: finding the fun…

Finding the Fun

As a term, I tend to think of it this way: when you first come up with an idea for a game, it’s entirely theoretical. You have an idea, and maybe the idea is written down, but as the game does not exist you can’t actually prove that the game will be enjoyable to play.

The process of going from “I think this game will be fun” to “I am confident this game is fun” is very personal and varies massively depending on the kind of game.

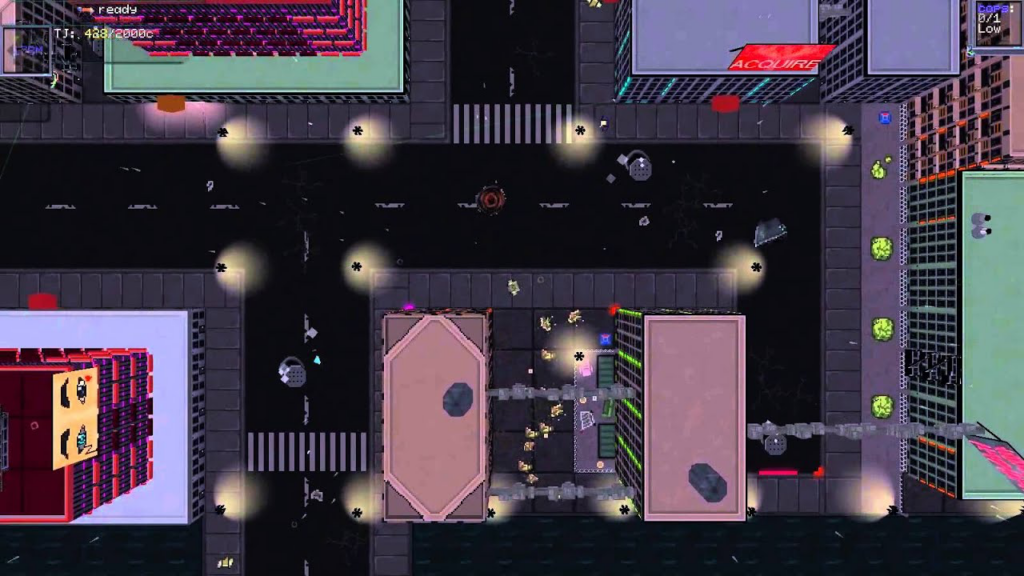

For instance, if you’re making a simple shooter or other action game, “finding the fun” may happen in a very early prototype – the moment you can move your pieces around in the game, even if they’re coloured blocks or temp art rather than final pieces. Sometimes, the “idea” for the game actually -does- come from a prototype.

In our 2014 game Metrocide, the core “fun” for us was what we found in a prototype that came from a game jam. The prototype lacked many of the graphical features and mechanics we’d add later, but the basic motion in the game world and the core game loop was there – and we thought it was fun enough to press on into making the full game happen.

Other times, the “fun” in your game isn’t as simple as “does it feel good to blast apart enemies with a laser gun?” or “does it feel good to engage in parkour throughout this representation of an ancient city?”. It can sometimes, especially in the case of strategy or management games, really not be something you can truly find until many of the game mechanics are fully implemented. I would imagine, for instance, that until many of your buildings and UI elements are in place and working, the real “fun” of a citybuilder might only be found much later in the development cycle.

…as it relates to Dungeons of Freeport

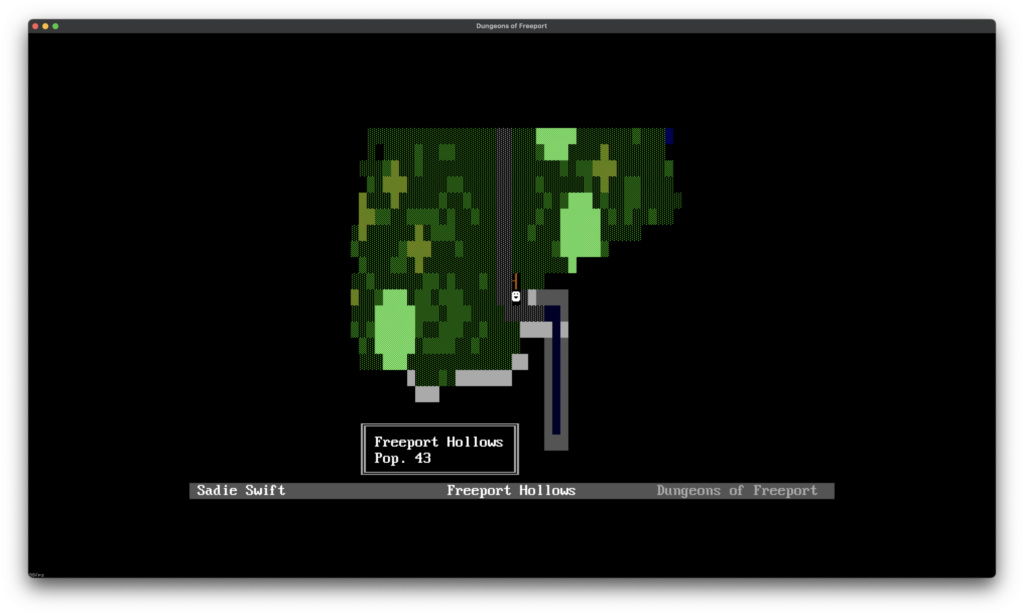

Dungeons began as a small side project while I kept on with my full time game dev job. It was as much for the joy of making it (and the challenge of coding a roguelike) as anything else. I had the core mechanics working within about 3-4 months including dungeon generation, and figured given it was just for myself, I’d finish it off with very basic ASCII/ANSI graphics (despite how this no doubt would reduce the number of people interested in playing the game) and drop it up on itch along with my other personal projects.

That was still my plan as I kept adding new features and polishing mechanics some months ago. Until, well… things changed. Not just my personal situation, which has very much changed for the better in the last little while – but things with Dungeons changed.

As I began to have something like the full game in terms of its core loop, I played it much more myself, and began to let friends play it too.

In I suppose a conventional sense, I found the “fun” pretty quickly with Dungeons. This was partly because I was working in a genre where the fun is pretty well established – a turn-based tile-based proc-gen roguelike is a known quantity, and the core loop of how they function has been refined and toyed with for over four decades now.

A lot of the time, in an established genre of game, if it ain’t broke, trying to fix it can actually just make it less fun. I tried to keep that in mind with Dungeons, and as a result with a few exceptions the core loop should be fairly familiar anyone who’s played other traditional roguelikes. It was also because I could get the guts of the game working without needing temp art or to spend an age building a custom map rendering engine – an advantage of making a text-mode game.

Maybe I forgot just how fun a Roguelike is? But for whatever reason, as I added my own little twists on it I found a game that I think was more accessible than I’d given it credit for.

Is the game more fun than I had expected? Eh, that’s very subjective and it’d be pretty arrogant of me to declare it so, even within the bounds of subjectivity. But it’s certainly something where my personal passion for it grew over time, including the realisation that I might potentially be able to interest more than just those who’d be up for a text-mode game.

Did this mean jettisoning the text aesthetics?

Well, I hope not. After all, it’s still part of the reason I get a silly-big grin when I open up the game and start poking around in the high ASCII. However, it’d be a tough sell to shove a game up on steam that requires people to futz around with their terminal settings to get the game to display right – and it’d write off any chance of me doing a decent version for Steamdeck or any other console.

So the last little while, I did what I think is the natural thing: I ported it to my little custom libSDL engine – Sapphia.

Grafficks!

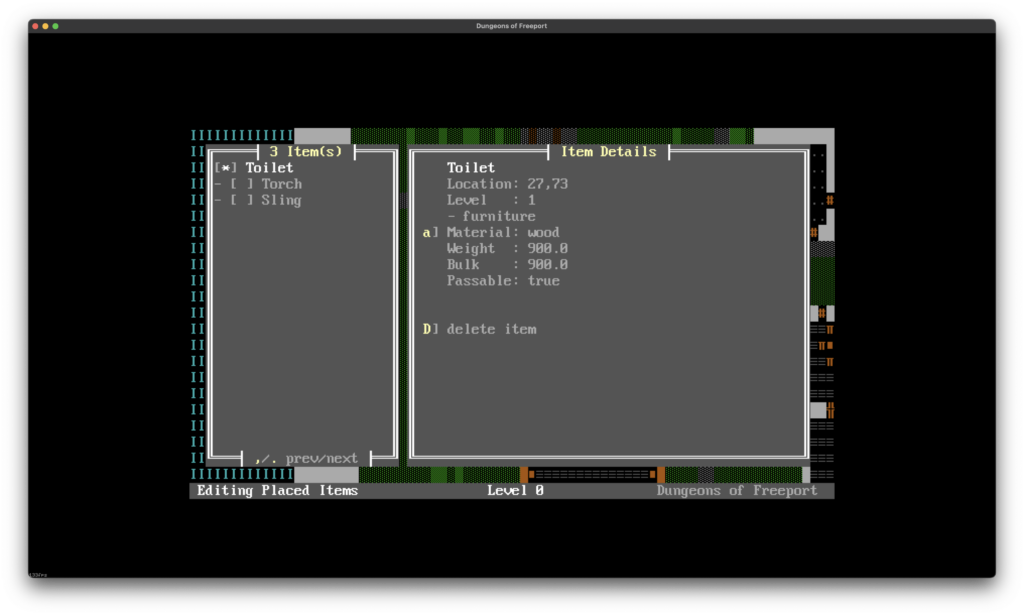

Dropping the game into my own little custom Virtual Screen renderer which shows code page 437 text was a good plan. It let me essentially drop the game’s renderer right on into the new system without man changes. It kept the charm of the ASCII graphics, but ensured that I could run the game on any system from Linux to Windows and ensure that what was appearing on the screen was 100% what I intended – no “sorry, your font is set wrong in the terminal” problems.

It even let me do a few things that would have been tougher before – for instance, the game now has full gamepad support. This was something I’d always intended (the game is built around a simple control scheme of movement plus a small number of ‘action’ buttons/keys, so it controls fine on gamepad) but it was always a little bit more annoying to try and do while I wasn’t using any nice cross-platform APIs such as this.

It has, however, put me at a bit of an impasse.

Limitations vs Freedom

My intention with Dungeons was always to keep both versions alive. I’d have the “Steam” version done using fake-terminal “graphics”, with the original text-mode version still available for those who wanted to not just play it in terminal mode, but to also play the game in the BBS “social game” format I used for Swords of Freeport.

Up until now, I appreciated the limitations being terminal-mode gave me. Restrictions, after all, can breed forced innovation – or at least force you to think simple. Scope creep gets tougher when you have extreme limitations on how the game can be controlled and presented.

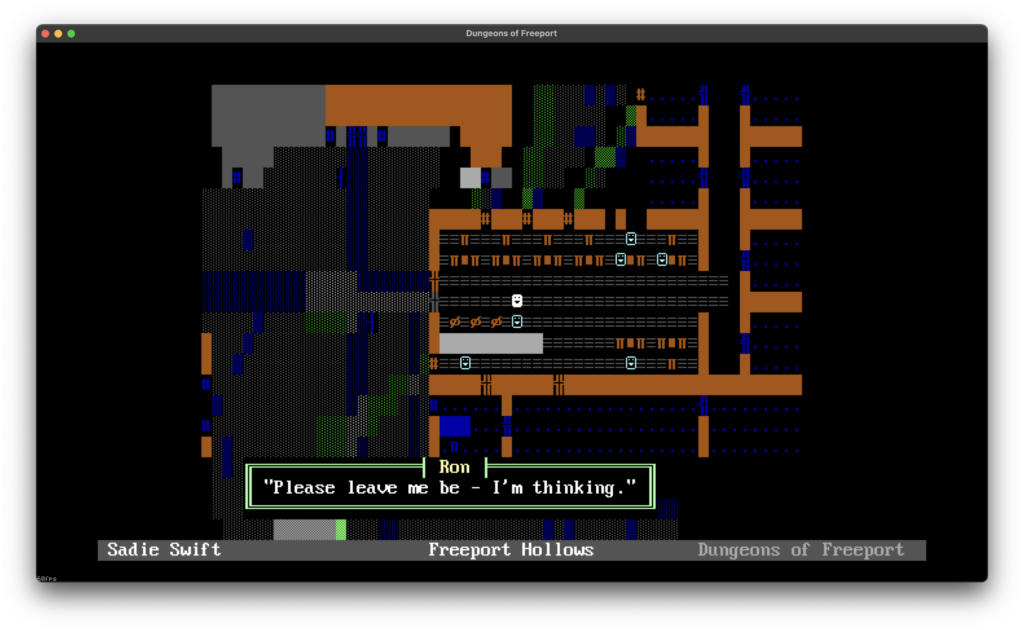

But every time someone plays it now, they love the look of the game… but ask a million questions.

“Can I do have the tree foliage fade when you move close to it?”

“Could you do have the mobs and NPCs move smoothly between tiles?”

The answer to all these questions, in the terminal version… was no. I simply could not, due to the limitations of the presentation medium.

But, like Dwarf Fortress or Brogue and many other roguelikes, I am not actually using “text mode”. There is no terminal any more. With my faux-terminal render… yes. I could. I would just have to change the render. Let it still look text-mode, but use some simple but nice effects to help bring the world to life just that little bit more.

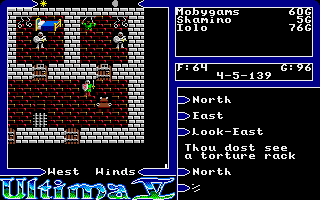

I had always thought I could do a second renderer – like, you switch live between a text-display and a simple graphical display throwing back to early Ultima games. The switching would be instant, akin to going between original graphics and the special edition re-imagined ones such as in the two Monkey Island special edition games.

The problem is the “real” terminal-mode version. The more I add, the fancier the features get, the less feasible maintaining the second version becomes. The limitations of terminal mode helped me early on in the game’s development, but are now hindering me. This includes optimisation. Re-drawing a virtual text screen means a bunch of things to help it push 4000 sprites on a full screen at once – and I essentially have to do that every single time the player moves one tile.

If I make a proper renderer, this difficulty all but vanishes, improving the game performance and giving me more freedom.

The last month, as I moved Dungeons over to the new renderer, I’ve kept all the old code. I knew it wasn’t going to build again without more work, but it’s all still there. ready for me to bring it back to life.

But the further I go… the tougher that looks. It’s especially rough with the acceptance that the overwhelming majority of whatever number of people actually play the game would never play the terminal mode – just a handful of us who still like BBS-style shared linux servers to play on.

Have I made a decision to cut the terminal mode?

No. I am still, for now, sticking to simply keeping my terminal code, hiding it behind #defines and build options. But the further I get into the fancy stuff I can do with my new SDL version… the more it seems like a jumping off point, rather than a thing I should dogmatically stick to.

(Especially as it frees me from 100% trying to write a functional gamepad-using game UI in 80×24 character text mode.)